The Synagogue as Civil Society, or

How We Can Understand the Shas Party

by

Omar Kamil

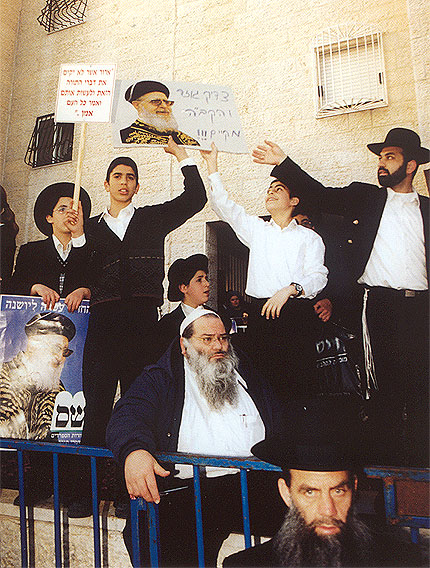

Shas supporters with posters of Shas spiritual leader, Rabbi Ovadia Yosef

from ha-Rav 'Ovadyah by Ronen Kedem, Yedi'ot Aharonot Books,

2002, page 163.

from

Mediterranean Quarterly

A Journal of Global Issues

Duke University Press

Volume 12, Number 3, Summer 2001

pages 128-143

We teach our children the things that are relevant to them: Jewish history, Sephardi religious customs, Torah, Mishna, Jewish values, and not the French Revolution.

—Senior Shas activist in an interview in Jerusalem, 19 April 2000

In the south of Israel, far from Tel Aviv and Jerusalem but not very far from Beer Sheva, lies the poor, sleepy town of Yeruham. In the 1999 Knesset elections, the results for Yeruham were clear: One Israel, 8.6 percent; Likud, 14.3 percent; Shas, 30.1 percent. Yeruham, which recently made headlines in Israel for its record unemployment figures (12.5 percent), was established in the 1950s as a "development town" 1 and is inhabited today mostly by the families of immigrants and their descendants from Arab and Islamic countries, the so-called Sephardim.2

Constituting about half the Israeli Jewish population,3 the Sephardim are regarded as being relatively poor and working-class, having a low social status, often living far from the main cities, and considering themselves religiously traditional (mesortim). Politically, in the 1950s they supported the dominant Ashkenazi-linked establishment, represented in Mapai. Since the middle of 1960s they have become a major political force by solidly voting for the Right, especially for the Herut (freedom), later Likud.4

Neither the Israeli political Left nor Right, which are both Ashkenazi, has succeeded in integrating the Sephardim into Israeli political, social, and economic life. The new hope of the Sephardim is called the Shas Party.5 Indeed, it is no exaggeration to say that Israeli political, social, and cultural development since 1983 cannot be fully comprehended without understanding the genesis and development of the power of Shas, the haredi Sephardi party.6 Formed in 1983, Shas won four Knesset seats in its first appearance at the polls. In the 17 May 1999 general election, it won a staggering 17 seats in the 120-seat Knesset, only two less than Likud, the second largest party (see table 1). It attracted support among the Sephardim who live in the country's poorest development towns and neighborhoods.

Table 1

Gains by the Shas Party in Israeli Elections since 1984

|

Year of elections |

Number of votes |

Percentage of overall vote |

Knesset Seats |

|

63,600 |

3.1 |

4 |

|

|

107,000 |

4.7 |

6 |

|

|

130,000 |

4.9 |

6 |

|

|

260,000 |

8.7 |

10 |

|

|

430,676 |

13.0 |

17 |

Source: Yoav Peled "Towards a Redefinition of Jewish Nationalism in Israel? The Enigma of Shas," Ethnic and Racial Studies 21, no.3 (1998): 703; Knesset homepage at, www.knesset.gov.il. [Web Editor's Note—In the 2003 Knesset Shas lost 6 seats but still held a respectable position even as the liberal parties made strong recoveries.]

In this essay I aim to explain the social success of Shas among the Sephardim. Within the framework of the civil society debate, I argue that Shas offers the Sephardi what the Israeli state fails to do: integration into Israeli society through a network of educational and social service institutions. Adopting political strategies akin to those used by Islamist movements throughout the Arab world, Shas penetrated the Israeli state by bypassing it. Through its activities, the leadership of Shas aims to create a new Jewish cultural identity based on the Sephardi Jewish custom (minhag).

The Civil Society Debate in the Middle East

The term civil society has had different meanings, not only in a theoretical framework but also in various social contexts.7 However, the expression is used today to indicate how groups, clubs, and organizations act as a buffer between state power and the citizen's life.

Civil society does not work as a "bubble" within the state but is strongly related to it. It cannot be regarded as a voluntary association within the state but as a state-free zone, with an alternative concept of social relations and social orders.8 With regard to the religious institutions and their functions as a part of civil societies, the debate on civil society in the Middle East, particularly, deals with the role of Islamist organizations.9 These include the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, Jordan, and Syria and the National Salvation Front in Algeria, for example. According to Baruch Kimmerling, where the state defines itself in Islamic terms, civil society defines itself in secular or other nonreligious terms, and vice-versa. The rise of civil societies in the Middle East has led to growing interest in state-society relations. Why does the state in the Middle East allow the development or the very existence of such societies? The answer to this differs from state to state.

In some societies the state is too weak to be able to prevent the appearance of a civil society; in other cases the state feels powerful enough not to perceive itself as threatened by the civil societies. However, the most interesting cases are those where the state succeeded in recruiting or coopting the civil society and its leadership to act as the overt or covert agents of the state.10

The debate over civil society deals almost exclusively with Arab and Islamic societies in the Middle East. I argue that the different organizations of the Shas Party function as a part of the civil society in Israel and were not only tolerated but even supported, at least from the middle of 1980s until the middle of 1990s, by the Israeli state. Thus, Shas' civil society was in a way autonomous so long as its goals did not conflict with the interests of the state. Only since the second half of the 1990s has the Israeli state taken more control of social and religious activities of Shas.

Furthermore, I argue that the civil society of the Shas Party—in contrast to the conventional sociological concept of society—is an active entity and not just a passive aggregate of people that possess some imagined collective identity. The leadership of the Shas Party aims to gain a kind of social reward for itself and the Sephardim as beneficiaries of the civil society of Shas. They hope to become a part of the establishment through their party's social activities and to move the Sephardim from a peripheral status to the center of Israeli society.

The Israeli Ashkenazi State and

Its Internal Other, the Sephardim

To understand why Shas is attractive to the Sephardim, one has to go back to the early years of the Israeli state, when hundreds of thousands of Jews from North Africa and the Middle East were pouring into the fledgling country. These new arrivals met a dominant and seemingly impregnable Ashkenazi establishment bent on shaping a "new" Jew, who would be secular and Western in outlook.11 In the process, the country's leaders ignored the cultural mores and traditions of the Sephardi Jews. Also, many of the Sephardim were sent to far-flung, undeveloped regions of the country, such as the Negev, where they were housed in transit camps and where infrastructure was thin and jobs scarce. Social dislocation soon followed as the family structure began to disintegrate and a growing number of young Sephardi men became involved in crime. The Ashkenazim who had established the state strove for a position for Israel in the Western world. The Sephardim, whatever Westernization they may have undergone, were disturbingly Oriental to Ashkenazi Jews. They were dark, they continued to adhere to much of their tradition, and their language had the guttural characteristics that German Maskilim12 had carefully removed from the Hebrew language.13

The Ashkenazi Left, which dominates political, social, economic, and cultural life in Israel, was torn between two cherished identity projects. On the one hand, they were deeply committed to Westernization, and the massive influx of Jews from the Levant could, as they saw it, drag Jewish society back to its not-too-distant Oriental state. On the other hand, they were equally deeply committed to free immigration of all Jews and hoped to make the new Oriental immigrants the state's Jewish laborers, and so they could not solve the problem by restricting the Sephardi influx. Indeed, the inferior standing of the Sephardim in Israeli society is not anchored in their supposed traditional Oriental culture but rather in the subordinate nature of their early encounters with the Ashkenazim in Israel. The structure of the relations between the Ashkenazim and Sephardim is a structure of dependency: senior positions in the business world, control of capital, dominance of the political institutions, and power to make decisions that determine the major directions of the development of the society as a whole are all in the hands of the Ashkenazim. The Sephardim, by and large, possess no capital, provide low-rank labor, and have relatively little representation in the corridors of political power. Consequentially, the Sephardim constitute a periphery to an Ashkenazi core.14

The Sephardim arrived in Israel as refugees, stripped of their material possessions, confused, and dispossessed. The educated among them were also deeply committed to Westernizing themselves and intended to underline their social distance from Israel's Arab neighbors. To construct them as Oriental, the Ashkenazi establishment used the same symbolic discourse that the Sephardi elite had themselves adopted, one which resonated with their sense of self. And just as the Ashkenazi internalization of the East-West dichotomy caused them to exclude Sephardim, so the Sephardi internalization of the same dichotomy paralyzed their ability to resist their own exclusion. Sephardi leaders not only believed in the construction of themselves as Eastern, they also believed that their Oriental identity was a legitimate reason for an inferior social position.15

Under the dominance of the Ashkenazi Left, Sephardim occupied a peripheral position in Israeli society and developed a hostility to those in dominance. The Israeli right wing under the leadership of the Ashkenazi politician Menachim Begin made use of this hostility. Begin brought the Sephardim onto his side in his political rivalry with the Ashkenazi Left. The Sephardim pinned their hopes on Begin, and they supported him up until the end of Ashkenazi political dominance in the Knesset elections of 1977. But at the beginning of the 1980s it was already clear to the Sephardim that Begin was not going to change their peripheral position in Israeli society, and they sought for an alternative political or social power to invest their hopes in anew.

Up until today the Israeli Ashkenazi establishment has been—according to the Sephardim point of view—sorely lacking in understanding. Stories of Yemenite Jews having their side locks cut off16 and of immigrants being sprayed with DDT on arrival in Israel became legendary.17 The sense of shame these immigrants felt about their identity and culture has been passed on to their children. One successful second-generation Sephardi public relations executive told me how his father used to hum Om Kolthom songs only in the privacy of his bathroom because he was too embarrassed to be heard humming the tunes of the legendary Egyptian singer in public. He also recalled the shame he felt when his grandmother fetched him from school dressed in traditional clothing. A young Sephardi journalist remembers how she was embarrassed to mention her family name when she first arrived at the university because she feared it identified her as Sephardi and might handicap her chances. Moroccan-born David Levy, a former foreign minister who rose from being a construction worker to the top ranks of the Likud leadership before recently teaming up with Labor leader Ehud Barak, once recalled how, when he and his friends were working in the kibbutz fields as hired help in the early years of the state, the kibbutz bosses callously ignored their requests to move their pail of drinking water out of the sun and into the shade.

To sum up, in their endeavor to Westernize Israeli society, the Ashkenazi establishment believed that the Sephardim had the potential to change the project fundamentally through Levantization. Struggling for a way of incorporating the new immigrants without losing ground on the Westernization project, the Ashkenazim resolved the dilemma by integrating the Sephardim into the lower levels of Israeli society, where their impact on the emerging identity, culture, and society would be minimal.

Shas as the Sephardi Alternative

Since its establishment in 1983, Shas has been a stable and increasingly powerful presence in the Israeli political and social arenas. Its electoral and social successes bewilder not only journalists but also social scientists.18 The reason for this confusion lies in the conventional methods that have been used for the analysis of Israeli political parties and interethnic Jewish relations.

There are three errors of analysis in the present literature about Shas:

1. The dichotomy of religious-Zionist versus religious-a(nti)-Zionist (haredi), which is usually used in Israeli social and political science to explain and analyze Israeli religious parties, is irrelevant in the case of Shas. This dichotomy is a product of Ashkenazi Judaism and helps us to understand only the religious Ashkenazim's view of their own relationship to Zionism and the state of Israel. Shas is a product of Sephardi Judaism, which is completely different to the Ashkenazi one. In order to understand the development of Shas as political and social movement, we must move away from this conventional analysis and try to understand Shas on its own terms, the Sephardi terms.

2. The labeling of Shas as a haredi party shows how analysis of the party is still in its infancy.19 The fact that most of Shas' leaders are graduates from educational institutions of the haredi party of Agudat Jesrael does not justify the classification of Shas, itself, as a haredi party. Haredi parties do not join any government coalitions in which they would bear collective ministerial responsibility for the rule of secular law, as opposed to the halacha, Jewish religious law. Unlike all true haredi parties, Shas has fully participated at cabinet level in all Israeli governments since the party's establishment. Also significantly different from other haredi parties is Shas' attitude toward Zionism. Whereas the conventional haredi parties reject Zionism as the ideology of the state of Israel, Shas aims to redefine a Zionist ideology based on secular elements into an ideology that is based only on the Sephardi interpretation of Judaism, the Sephardi minhag.

3. Some scholars see Shas as a right-wing, extreme party, while others see Shas as moderate and left-oriented. Scholars of the first group substantiate their view by referring to the attitude of Shas toward domestic Israeli affairs. For the second group of scholars, the Response of pikuah nefesh20 of Rabbi Ovadia Yossef, the head of the Shas Council of Sages, serves as a basis for their opinion.

The political behavior of the Shas party cannot be pigeonholed as either Right or Left (commonly referred to as "extremist" and "moderate," respectively, in Israeli political science circles). Shas has joined Israeli governments of both the Left and the Right and has sat in government with the secularist-left Meretz party. The presence of Meretz members in the cabinet was a factor cited by other religious (Ashkenazi) parties among their reasons for not joining the government.

To sum up, I stress that the leadership of Shas take a pragmatic political course that allows the party to place itself outside the left-right dichotomy and to find a modus vivendi with all other Israeli parties.

For some scholars, Shas embodies a Sephardi-ethnic party with a message of a separatist nature. However, the fact that the bulk of Shas voters are Sephardim does not mean that Shas is an ethnic party with an ethnic-separatist message. The adjective Sephardi has for Shas only a religious meaning. Certainly, Shas aims to reestablish the dominance of Sephardi Jewish religious rulings against the currently dominant "other." That other, however, is not the Ashkenazim in general but the Zionist, especially the Labor Zionist establishment and the completely politicized Ashkenazi religious establishment, which has marginalized—in various ways—the Sephardim since the beginning of the Zionist settlement of Palestine.21 Rabbi Yossef's wisdom and simultaneously his secret of success lies in his ability to mobilize his supporters not against the Ashkenazi ideology in general but rather against the secular and non-Jewish components of that ideology.

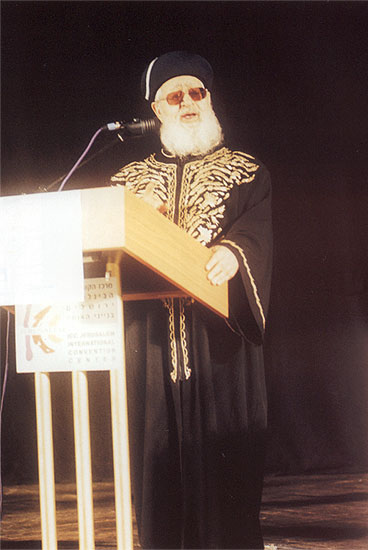

Former Chief Sephardic Rabbi of Israel and spiritual head of the Shas Party, Rabbi Ovadia Yosef,

from ha-Rav 'Ovadyah by Ronen Kedem,Yedi'ot Aharonot Books, 2002, page 88.

The leadership of Shas stresses the social, political, and economic inequality between the Sephardim and the Ashkenazim. As a political party and a social movement, Shas holds to the idea that not just the Ashkenazi Left but both the whole Ashkenazi Zionist-secular establishment and the Ashkenazi religious establishment are responsible for the peripheral position of the Sephardim in Israeli society. Both secular and religious Ashkenazi establishments have cut the Sephardim off from their cultural, religious, and traditional roots and placed them in inferior and peripheral status in the society.

Shas "reveals" to the Sephardim an alternative way, in which all Jews of Israel, both Ashkenazim and Sephardim, can be unified under the crown of the Torah as it is interpreted in Sephardi Judaism. This different way of Shas is—in the eyes of the Sephardim—not just a spiritual and moral matter. The Sephardim hope thus to benefit socially and economically, and because of that, they support the Shas Party with enthusiasm.

The Synagogue as Civil Society

The synagogue was for Sephardim in Arab and Islamic countries more than a place of worship. Sephardi synagogues had a social dimension, for the entire social life of the Sephardim took place there. Community activities such as marriages, exchange of information, social gatherings, medical care, religious study, and so on took place at the synagogue. Membership of a synagogue conveyed to the Sephardim a feeling of unity and security.

When the Sephardim came to Israel, they encountered a secularized Israeli society that bewildered them. Looking for security and a confidential atmosphere, the Sephardim turned to the Ashkenazi synagogues, which were completely institutionalized and politicized and were not able to offer the Sephardim any kind of support. Today, synagogues under the control of Shas offer the Sephardim everything that the Ashkenazi synagogues were not able to offer then and function as a social and religious home.

The civil society of Shas is self-contained in its own community and centered in synagogues based on Jewish fraternities. The recipe for success of these civil societies is very simple: offer help to everyone who needs it. In order to realize this motto, Shas established an independent educational system, religious schools, synagogues, and mikvaot (ritual baths). It rehabilitated delinquents and drug addicts, provided support for large families, created jobs, and improved housing.22

Where the state fails to offer acceptable living conditions in the peripheries and slums, Shas' civil society is very active. For one of the Likud's most active loyalists in Beer Sheva,23 Yossi Gozlan, Shas turned the south of the country into its first priority national project.

They [the Shas members] are everywhere . . . Every time there is a problem in Be'er Sheva or in any of the neighboring towns, one of their ministers is sure to show up and offer help. They know how to take care of their own. It would be no exaggeration if I were to tell you that when the next elections roll around, they will increase their Knesset representation to 20 or more seats. It's very simple. Shas does what the rest of the country is sick of doing.24

The relations between the civil society of Shas and the Israeli state can be divided into two phases. The first phase began in the second half of the 1980s and continued until the middle of 1990s. In this period the state was absolutely sure that it had Shas and its civil society under control. Based on a model of state-society relations, Gal Levi has analyzed the behavior of Shas toward the Israeli state and vice versa. According to Levi, the state sees Shas and therefore its civil society as acting in the interest of the state.25 In order to "beat" the extreme national militant-religious movement Gush Emunim (Bloc of the Faithful)26 and the left-leaning ethnic identity promoted by secular Sephardi movements, the state welcomed and supported the moderate traditional religious tendency of the Shas Party and its civil society as an alternative. Shas received financial support from both left-wing and right-wing governments in Israel and with the help of this money extended the activities of its civil society. Indeed, the appearance of Shas on the Israeli stage led to a reduction in the number of supporters of Gush Emunim and the Sephardic ultrasecular groups.

No Israeli government has been able to engage in conflict with this new political and social power, since Shas has consolidated its position in Israeli social and political life. Because the two big parties in Israel, Likud and Labor, are not ready to govern together, Shas has managed to hold the balance of the power and consequently increased its electoral record over the past seventeen years. The price that Shas has consistently demanded for its participation in government has been considerable financial support, which flowed mostly into the social activities. With the governmental funds, Shas has been able to build an excellent network of social and educational activities under the name El hama'ayan (To the Wellspring), which is represented throughout the country. The Israeli state was overburdened and welcomed volunteer activities from all religious parties, because such activities are not perceived as subversive to the state and its basic interests.

But Shas felt powerful enough to take a dissident stance and tried through its civil society to realize its version of an Israeli identity based on Sephardi custom among the Israeli public. This aim of Shas contradicts those of the state, which always foresaw an Israeli identity based only on the values of Zionism.

In the second half of 1990s, the state began to see Shas as a threat to its interests. The Israeli state's answer to the activities of the Shas civil society went in two directions: first, to restrict state financial support of Shas, and second, to declare the improving of the social status of the Sephardim as the most urgent task of the state. In order to wither Shas, the Israeli government of Prime Minister Ehud Barak began by putting brakes on the state's financial contribution to the Shas civil society. This drying-out policy was not effective, because Shas as one of the central political forces in the land threw its whole political weight into the fight against it.

It was also Barak who placed the social problems of the Sephardim at the top of the Labor Party's agenda. In June 1997, in a surprise move by Labor, its convention was held not on its home ground in Tel Aviv but on the arid soil of the development town Netivot, which is inhabited by Sephardim. On that occasion Barak, who succeeded Simon Peres as party leader, gave an important opening speech in which he begged forgiveness of the Sephardi immigrants on behalf of the Labor movement and promised to do all he could to improve their disadvantaged status in Israeli society.27 After his election as prime minister in May 1999, however, Barak concentrated on the peace process and neglected a social agenda. The failure of Barak's government to take effective measures to improve the social life of the Sephardim has meant more and more success for Shas civil society.

The Message

On Kanfei Nesharim Street, near the haredi Har Nof neighborhood in Jerusalem, is located the headquarters of the Shas' educational network, called Ma'ayan Hahinuch Hatorani (the Wellspring of Torah Education). A group of very active rabbis manages the network. These include Yehuda Cohen, head of the Yakir-Yerusalalyim (Knowledge of Jerusalem) yeshiva; Eliahu Abba Shaul, son of Rabbi Benzion Abba Shaul, who was previously the president of the network; Reuven Dangur and Shmuel Pinhasi (head of a yeshiva and rabbi of a Jerusalem synagogue, respectively); Rueven Elbaz, head of the Or Haim (Light of the Life) institution; and the administration's chairman, Moshe Maya, formerly a Shas member of the Knesset and currently member of the party's Council of Torah Sages.28 With a budget of approximately $50 million and with more than forty thousand children in kindergartens, elementary schools, and other educational institutions all over Israel, Ma'ayan Hahinuch Hatorani is a serious challenger to the state educational system. According to Shas figures released in early 1999, the party's educational network includes 146 elementary schools nationwide, 682 kindergartens, 50 junior high schools, and 86 day-care centers. Shas also claims to have a total of twenty-four hundred school teachers, principals, and supervisors and an additional twenty-two hundred kindergarten teachers and teacher aides. Education ministry figures are lower, but they, too, testify to the vibrancy of the Shas educational network.

With what Yossi Dahan has called the ideology of "chocolate milk and a roll,"29 Ma'ayan Hahinuch Hatorani attracts more and more children from secular and traditional religious families. The fact that these schools offer low tuition fees, free transportation, meals, and a full school day—state-run schools end instruction at 1 P.M.—make them very attractive for working parents. For a fee of just $250 per month, far less than any public school, Shas schools offer a school day three hours longer than the public schools'.30 The Shas system provides students with transportation to and from school and a hot lunch at very low prices, sometimes even free, depending on the number of children in the family and the parents' financial situation. Further, these schools offer adult-education classes, tutors for Bar Mitzvahs, women's support groups, youth activities, immigrant absorption programs, and scholarships for yeshiva students.31

Successive governments have been happy to buy Shas' political support since 1983 in exchange for allowing the party to build a vibrant educational network that is state funded but not state supervised and in which pupils are encouraged to show allegiance to rabbis rather than the state. Indeed, just one visit to any school run by Ma'ayan Hahinuch Hatorani is enough to gain an understanding of the aims and goals of Shas. Inside the classrooms, the walls are decorated with pictures of famous Sephardi rabbis. In the spot normally reserved for a portrait of the president or prime minister, pictures of Sephardi sages adorn the walls, including the mandatory poster of Ovadia Yossef, the spiritual leader of the Shas party, and a picture of cabbalist Yitzhak Kedouri. There are also quotations from the Old Testament. These images reflect the goals and aims of the Shas school system: the revival of the Sephardi religious custom, which should then serve as the basis of Sephardi cultural identity as Shas understands it. The tools for achieving this goal are to be found in the curriculum.

In the schools run by Ma'ayan Hahinuch Hatorani, religious studies are given priority. The school day begins with the morning shaharit prayer. Lessons begin about forty-five minutes later. The subjects: Mishna, Halacha, Talmud, Hebrew language, and Sephardi Jewish history. Limudei holini (secular studies), which include English, mathematics, natural sciences, geography, and history but not sociology or philosophy, are less important and are covered in three hours per day. In state-system schools that have adapted the long school day, the afternoon period is used to offer students help with homework, tutoring, and various extracurricular activities. In the Shas schools, students devote time to secular studies only after a full day of religious studies.

The goal of the Ma'ayan Hahinuch Hatorani is clear: while the state school system offers the "sons of the Israeli people" non-Jewish studies, the Shas school system educates a new generation into Sephardi Jewish values.

Conclusion

This essay has looked at the social activities of the Shas Party within the framework of the civil society debate. It has explained the social successes of the Shas Party within a model of state-society relationship. According to this model, the state assisted in the creation of Shas as a moderate alternative to both the militant Zionism of the radical religious nationalist Gush Emunim movement and the "ultrasecular," leftist ethnic identity promoted by the secular Sephardi movement. In addition, the state has been happy to buy Shas' political support over the past seventeen years by allowing the party to build a vibrant social and educational network that is state funded but not state supervised. On the other hand, as the debate on civil society in the Middle East has shown, Shas has built its civil society for and with the help of the Sephardim, an ethnic and peripheral group within Jewish Israeli society. The Shas Party offered a new cultural identity that attracted Sephardim. Through this new identity the Sephardim hope to improve their social, political, and economic status in Israel and to move from their current peripheral position to the center of the society.

With its social and educational network, Shas offers the Sephardim in the less developed towns and in the slums and poor neighborhoods of the big cities different kinds of educational, social, and economic support. It aims to challenge the state's social order through a new Jewish-Israeli identity based on Sephardi customs.

The continued growth of Shas may depend on the type of economic and social policies the state of Israel chooses to adopt in the coming years. The present policy of vigorous privatization offers little solace to those at the bottom of the economic ladder. If this process continues unabated, and is accompanied by growing unemployment and continued cuts in social benefits, the gaps between rich and poor, between center and periphery, will continue to widen, expanding the possible support base of Shas as the party of the dispossessed.

As Shas' power has grown, there have been calls for a government program to reverse the social split that Israel has been experiencing recently and that the party feeds off. That would require mass investment in education and infrastructure—especially in the country's outlying areas—so as to offer those in the lower classes the possibility of upward mobility. It would also require a more inclusive, sensitive approach to traditional Sephardi culture and identity.

Official Shas Party Website

back to top

About the Author

Omar Kamil is a doctoral candidate at the Institute of Political Science, University of Leipzig, Germany.

Further Reading on the Shas Party

Redefining Religious Zionism: Shas' Ethno-Politics by Aaron Willis

Shas—The Sephardic Torah Guardians: Religious "Movement" and Political Power by Aaron P. Willis

Rabbi Ovadia Yosef and his "Culture War" in Israel by Omar Kamil

Notes

1. The Israeli development towns are small urban settlements, located mostly in outlying areas of the country, that were established in the 1950s and 1960s and populated largely with Sephardi immigrants. See E. Ben-Zadok and G. Goldberg, "Voting Patterns of Oriental Jews in Development Towns," Jerusalem Quarterly, no. 32 (1984): 16-27; Yoav Peled, "Ethnic Exclusionism in the Periphery: The Case of Oriental Jews in Israel's Development Towns," Ethnic and Racial Studies 13, no. 3 (1990): 345-67. For the current situation of the development towns, see also the reports of the Israeli journalist Daniel Ben Simon, all in Hebrew: "The Remains of the Day: Ofra and Nitivot on the Day before the Elections," Haaretz, 20 May 1999; "The Winter of Their Discontent: Beer Sheva and Ehud Barak after the Elections," Haaretz, 25 February 2000; "Glazed Eyes and Feet of Clay: Yeruham and the Closing of Its Ceramics Factory," Haaretz, 24 March 2000.

2. Sephardi (Sephardim in the plural) is one of the most debatable terms in Israeli sociology. The term's meaning is literally "Jews who came originally from Spain." In the Israeli context nowadays, there is a difference between what Shas and its supporters understand by Sephardi and what the rest of the secular public understands. When the leaders of Shas speak of the Sephardim, they intend to emphasize the importance of Spanish Jewish customs (minhag) as opposed to the Ashkenazi customs as the authentic one for all Jews in Israel. From the point of view of Ashkenazi Israelis, Sephardim means Jews who came from Spain and from Arab and Muslim countries. The Jews of Spanish origin called themselves "pure-bred Sephardi" (Sephardi tahor). The "pure Sephardim" considered themselves a separate population, distinct from and above Jews who had arrived in the Holy Land from Arab and Muslim countries. In this treatise I prefer to use the term Sephardim instead of others such as Mizrahim or oriental Jews simply because it is the term with which Shas identifies itself. See Haaretz 31 August 2000; Daniel J. Elazar, The Other Jews: The Sephardim Today (New York: Basic Books, 1989), 15.

3. See Sami Shalom Chetreet, "Mizrahi Politics in Israel: Between Integration and Alternative," Journal of Palestine Studies 29, no.4 (2000): 51-63; Youseff Courbage, "Reshuffling the Demographic Cards in Israel/Palestine," Journal of Palestine Studies 28, no.4 (1999): 21-39.

4. For the electoral behavior of the Sephardim, see Shlomo Swirski, "The Mizrachi Jews in Israel: Why Many Tilted Toward Begin?" Dissent, no.31 (1984): 77-91; Hanna Herzog, "Penetrating the System: The Politics of Collective Identities," in The Elections in Israel, ed. Asher Arian and Michal Shamir (Albany, N.Y.: SUNY Press, 1992), 81-102.

5. Shas is derived from the Hebrew Sephardim Shomerei Torah, meaning literally "Sephardi Torah Guardians." Shas is also an another name for Talmud, which is itself short for "the six orders of Mishna."

6. Haredi (plural haredim) means literally "God-fearing." I use the term in order to avoid the inexact English "ultraorthodox believer," as it emphasizes that the reference is more to a way of life than an ultra-extreme theological commitment.

7. It is not my aim to augment the discussion about the civil society with more theoretical aspects. Rather, I use the results of the debate about civil society as a theoretical framework that could help us understand the successes of Shas among the Sephardim.

8. Baruch Kimmerling, "Elites and Civil Societies in the Middle East," in Elites, Minorities and Economic Growth, ed. Elise S. Brezis and Peter Temin (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1999), 55-64.

9. J. Schwedler, ed., Toward Civil Society in the Middle East? A Primer (Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Reinner, 1995), 13-5.

10. Kimmerling, "Elites and Civil Societies," 58.

11. See Baruch Kimmerling, The Invention and Decline of Israeliness: State, Culture and Military in Israel (Los Angeles and Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 13; Joseph Massad, "Zionism's Internal Others: Israel and the Oriental Jews," Journal of Palestine Studies 25, no.4 (1996): 53-68; Hannan Hever, "Mapping Literary Spaces: Territory and Violence in Israeli Literature," in Mapping Jewish Identities, ed. L. J. Silberstein (New York: New York University Press, 2000), 201-19.

12. The Maskilim ("the enlightened ones" in Hebrew) were eighteenth and nineteenth-century Jews who engaged in secular rationalistic studies and facilitated the acculturation of Jews to Western society. They were members of the Jewish enlightenment (haskalah).

13. For the dealings of the Ashkenazim with their Sephardi counterparts in the 1950s and 1960s, see Shlomo Swirski, Israel: The Oriental Majority (London: Zed, 1989), 1-26; Massad, 54-9; and R. Shapiro, "Zionism and Its Oriental Subjects, Part 1: The Oriental Jews in Zionism's Dialectical Contradictions," Khamsin 5 (1978): 5-33.

14. Shlomo Swirski and S. Katzir, "Ashkenazim and Mizrahim: Dependency in the Making," Notebook for Research and Critique (Hebrew) (October 2000): 21-59.

15. See s. Ballas, "I Am an Arab Jew," New Outlook 34, no.6 (1991): 30-3; Peter Demant, "Israel on the Orient Express," New Outlook 34, no. 6 (1991): 16-8.

16. See Aaron Willis, "Sephardic Torah Guardians: Ritual and the Politics of Piety," unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Princeton University, 1993, 132.

17. On their arrival in Israel in the 1950s and 1960s, the Sephardim were "disinfected" with DDT by workers from the Israeli health ministry. Many of the Sephardim believed that the health officials did so with humiliating disdain. Such "sins" against the new immigrants are generally considered to be the origin of the Oriental resentment toward the Ashkenazi establishment. See G. N. Giladi, Discord in Zion (London: Scorpion, 1990), 103-10; Shlomo Ben Ami, interview in Haaretz, 23 May 1997; Sami Michael, interview by the author in Ramat Golda, 4 June 2000; Shimon Ballas, interview by the author, Tel Aviv, 16 March 2000.

18. See Peled, 703-27.

19. Previous works written about Shas have been a doctoral dissertation (see Willis) and two master's theses. See Amir Horkin, "Political Mobilization, Ethnicity, Religiosity and Voting for the Shas Movement," MA thesis, Department of Political Science, Tel Aviv University, 1993 (Hebrew); Gal Levi, "And thanks to the Ashkenazim. . . . The politics of Mizrahi Ethnicity in Israel," MA thesis, Department of Political Science, Tel Aviv University, 1995 (Hebrew). None of them has been published so far. The only publication has been Peled, "Towards a Redefinition."

20. According to pikuah nefesh, the saving of individual life is of greater importance than other religious commandments that might lead to the sacrifice of the same life. Asked his opinion about a possible withdrawal from the occupied territories, Rabbi Yossef, in one of his most important responses, supported a withdrawal in order to save Jewish life. For the details of his response, see E. Kopelowitz and M. Diamond, "Religion That Strengthens Democracy: An Analysis of Religious Political Strategies in Israel," Theory and Society 27, no. 5 (1998): 671-707.

21. Peled, 720.

22. Chetreet, 58.

23. Beer Sheva is one of the development towns in Israel and the capital of the Negev region. The results of the last Knesset elections 1999 were clear: Shas, 22 percent; One Israel, 15.2 percent; Likud, 13.6; and Meretz, 4.1 percent. See Ben Simon, "The Winter."

24. Yossi Gozlan quoted in ibid.

25. See Levi, 2-12.

26. Vast amounts of literature exist on Gush Emunim as an ideology and a social movement. Here I shall mention only some prominent works. I. Lustick, For the Land and the Lord: Jewish Fundamentalism in Israel (New York: Council of Foreign Relations, 1988); G. Aran, The Beginning of the Road from Religious Zionism to Zionist Religion, Studies in Contemporary Jewry, vol. 2 (Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press, 1985); D. Weisburd, Jewish Settler Violence: Deviance as a Social Reaction (University Park, Penna.: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1989).

27. Yossi Klein Halevi, "I'm Sorry," Jerusalem Report, 30 October 1997, 8-12,

28. This list of the administrative team of Ma'ayan Hahinuch Hatorani shows that there is no professional pedagogue among the rabbis.

29. Yossi Dahan, Jerusalem Post, 15 August 2000.

30. For the 2000-1 school year, the fees of the public schools are about 1,300 Shekel. See Haaretz, 15 September 2000.

31. Willis, 195.

Web Editor's Note

This document has been edited slightly to conform to American stylistic, punctuation and hypertext conventions. No further changes to the text have been made.

This document is best viewed with 1024x768 pixel screen area.

Reprinted in accordance with U.S. copyright law.

Alabaster's Archive