Redefining Religious Zionism: Shas' Ethno-Politics

by

Aaron Willis

Princeton University

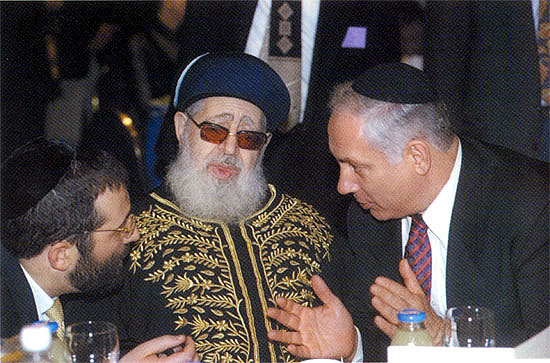

Former Chief Sephardic Rabbi of Israel and spiritual leader of the Shas Party, Rabbi Ovadia Yosef

from ha-Rav 'Ovadyah by Ronen Kedem, Yedi'ot Aharonot Books, 2002, page 62.

from

Israel Studies Bulletin

a publication of The Association for Israel Studies

Middle East Center

University of Pennsylvania

Volume 8, Number 1

Fall 1992

pages 3-8

ISSN 1065-7711

In the 1950's and 1960's when Jews from the Middle Eastern countries immigrated to the nascent Israeli state, they encountered a variety of ideological and institutional possibilities for assimilation. The various options were products of debates developed largely in Europe a half-century earlier. While many Middle Eastern Jews adopted the secular socialist values of Mapai Zionism, a great number also came to support a Zionism based on religious principles, a "religious Zionism." The National Religious party (Mafdal) offered these immigrants both ideological as well as material support for their "absorption" into Israeli society. As the official link to the state, the party helped Middle Eastern Jews in development towns and agricultural settlements by providing money for the purchase of Torah scrolls and the building of synagogues and ritual baths. The Mafdal also established a youth movement and nation-wide system of schools which played a significant role in the assimilation of the younger generation to the values and principles of religious Zionism. The Mafdal had a distinctly European (Ashkenazi) flavor, and many immigrants viewed successful absorption into mainstream society as necessitating the abandonment of traditional "ethnic" customs and norms in favor of Ashkenazi cultural models.

More than a generation later, the political party of Sephardic Torah Guardians (Shas) has risen to power with the claim that the material and spiritual needs of the Middle Eastern communities have been neglected. They blame the secular, and national-religious, Ashkenazi establishment. Appealing to Sephardic voters in the disadvantaged development towns and urban neighborhoods, Shas has promised to revitalize the condition of Sephardic Jewry in Israel through a program of religious education and social renewal. Campaign promises in the recent election echoed those of the early Mafdal: more money for ritual baths, synagogues, and religious education. Now however, leading rabbis came to urge the faithful to send their children to Shas' Torah day-schools rather than the state-run (Mafdal) schools. According to Shas sources, the watered-down religious values embodied by the Mafdal schools had led Israel's Sephardic communities to the abandonment of religious principles.

With a solid electoral victory behind it, Shas is now a critical partner in the governing coalition. It has inherited the instrumental position which Mafdal had maintained in the early years of the state, helping the Labor party to form a majority government. In 1992 Mafdal has opted to sit in opposition to the Labor-led coalition, having drifted to the "right" over the past twenty years through the influence of ideologically-driven Ashkenazi elements within its ranks. Shas has taken up positions in the Ministries of Interior, Religion, Education, and Finance, and now has influence over agencies that were, since the founding of the state, the power base of Mafdal. In political terms, Shas is well positioned to replace the Mafdal as the defining force in religion/state relations for years to come.

Whether Shas is a "religious-Zionist" movement depends on how we define our terms. A break-away faction from the "non-Zionist" Agudat Yisrael party, Shas' Zionist credentials have been called into question. The distinction between Zionist and non-Zionist religious movements has been emphasized by Israel

Shas is well positioned to replace the Mafdal as the defining force in religion/state relations for years to come.

scholars interested in demonstrating the diversity of "orthodox" attitudes toward the state. The "Zionists," institutionally represented by the Mafdal, are said to embrace the state as part of the messianic process leading to the eventual redemption of the Jewish people. The "non-Zionists," in this case the haredi (ultra-orthodox) Agudah, argue that the secular principles of Zionism only act to delay the messianic process. Jews remain spiritually in a state of "exile," regardless of the fact that they have physically assembled in the Land of Israel (nominally part of the messianic process). While the distinction is largely theological, the debate has been given political and institutional form via arguments about the rights of certain roups to make claims upon the state. Shas' label as a "non-Zionist" party is thus much more than a question of categorization. It is a political issue of the first order which has been the cause of vigorous debate within the Israeli body politic.

I argue that the traditional distinction between Zionist and non-Zionist religious ideologies is largely irrelevant to the understanding of Shas as an ethno-religious movement. The distinction is one which comes to us from debates within the Ashkenazi world, and helps us little to understand the logic of a movement

Shas has never labeled itself a non-Zionist movement. Rather, the leadership argues that the appellalion of "non-Zionism" has been used to deprive the movement of legitimacy within the wider Israeli public.

driven by ethno-religious principles of identification. Based on Shas' institutional position in the new government, and an understanding of the values which drive the movement, I suggest that Shas may represent a new style of religious Zionism which combines elements of both Agudah suspicion, as well as Mafdal enthusiasm, for the state. However, in order to make this claim, we must move away from traditional analytic categories and try to understand Shas in its own terms.

Non-Zionist politics?

Shas has never labeled itself a non-Zionist movement. Rather, the leadership argues that the appellation of "non-Zionism" has been used to deprive the movement of legitimacy within the wider Israeli public. Shas' attacks have focused in particular on the secular press. For example, in a pre-election Maariv article about Shas' efforts to gain votes in the Arab sector, Deri was pictured in a photo superimposed over a leaflet in Arabic. Under the photo, printed in Hebrew, read "You see, we are both non-Zionists" suggesting a direct quote from the Arabic leaflet. However, the unattributed quotation turned out to be from someone who "speculated" what might have been said between Deri and the Arab leadership. The juxtaposition of photo and text helped to further the sense that Shas is more with "them" (the Arab non-Zionists) than with "us" (the Jewish Zionists). It was a clear distortion of Shas' message.

Shas' sense of embattlement with the secular media has been exacerbated by the publication of details about police investigations into the Shas leadership. This includes accusations against Interior Minister Deri for fraud and the mismanagement of public funds for personal use. Shag has complained that the Police leaked detailed information directly to the press in an effort to discredit the movement. They have emphasized the fact that even after two years of investigation and thousands questioned no official charges have been brought. Deri has complained that he has been tried in the "secular" and "Ashkenazi" press by rumor and innuendo. The party used this sense of persecution to its advantage in recent election propaganda. The assertion of media collusion with investigations argued to be politically motivated, helped to further the sense of discrimination, so important to Shas' message of pan-Sephardic unity.

Also, in the popular press much has been made of the fact the members of Israel's haredi (ultra-orthodox) population are "exempt" from army service as long as they remain in their yeshivot (religious schools). With army service seen as an important marker of patriotic duty in Israeli society, those who seek deferments are viewed with suspicion. Because Shas openly supports the deferment from army service for those studying in religious institutions, it has facilitated the impression that the movement is not really a full participant in the Zionist project.

Shas' purported non-Zionism has also been used against the party in more overtly political contexts. As a result of agreements putting together the new government, a separate Authority has been created in the Education ministry which will supervise all haredi education. It will be run under the supervision of a Shas Knesset member and will guarantee that haredi schools receive adequate funding from the Ministry as a whole. Arguing against the establishment of this special Authority, a Mafdal leader complained that the haredi system did not deserve the government attention "because of their anti-Zionist attitude. They do not teach Zionist history nor observe national holidays," he charged.

Identity politics

Shas has built a successful movement on the notion of a pan-Sephardic identity. Drawing upon experiences of social and cultural marginalization after immigration, they have forged a sense of common Sephardic experience, bring in groups who are not technically Sephardic (i.e. Spanish descended), but Middle Eastern more generally. With recent history projected back onto the glorious age of Sephardic Jewry, the Shas leadership has worked hard to combine the diversity of Middle Eastern customs and historical memories, into what I am calling a unified "Sephardism." With reference to this sense of common experience and group identity we can better understand the "political" policies of Shas.

Certainly the most divisive issue between Right and Left in the recent election campaign was the future of the occupied territories. While the Right supported an ideology of "greater Israel," the Left argued for "territorial compromise" as part of a general re-ordering of domestic priorities. During the election campaign Shas argued in favor of a coalition with the Right (Likud). Less than a week after the election, Shas signed an agreement with the Left (Labor-Meretz). The focus on Shas as driven by identity as opposed to ideology helps to explain why it was able to shift gears so easily.

Rabbi Ovadia Yosef with Likud Party Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu and Shas Interior Minister,

Aryeh Deri,

from ha-Tsalash ha-shishi : behirot '99—ha-sipur ha-male by Hanan Kristal,

Keter Books, 1999.

Ovadia Yosef, the Shas spiritual leader, is widely regarded as a dove on the matter of territorial compromise. He has come out with a halachic ruling which states that the mitzvah of saving lives (pekuach nephesh) makes it permissible to relinquish parts of the historical land of Israel from Jewish control. He concludes that it is really a matter for the generals to decide which course will save more lives. Yosef himself was born in Iraq and served as the Chief Rabbi in Cairo for several years. As a former member of the Jewish elite in the Arab world, Yosef positions himself as a link for the resumption of good relations between the Arab and Jewish leadership. He has visited in both Egypt and Morocco, had audiences with the highest officials, and made statements encouraging a then stalled peace process. His position has thus been described as a product of identification with the elite status that he once held, based upon memories of generally good relations between the Arab leadership and himself.

Analysts have found Yosef's position to be in tension with the vast majority of Shas supporters, whose attitudes are believed to be more hawkish. This apparent contradiction has puzzled many, but the Shas leadership claims that it is a non-issue. One leader argued that Shas' position on territorial compromise is irrelevant to its guiding mission:

Shas was created to spread Torah in the Sephardic communities. We have promised more education and more money for ritual baths. We do not take a stand on the issue of the territories because it would not make sense. Some of our people want to return land and others do not. It is not connected to the Sephardim . . .

The appeal to a pan-Sephardic identity renders the discussion on territorial compromise secondary . Rather, the desire for individual redemption and social renewal become the driving force in the logic of "Sephardism."

A constituency of supporters and opponents of territorial compromise may seem like a tenuous marriage of convenience bound to break down when ultimate decisions are to be made. But if we examine the question in terms of identity, as opposed to the clash of ideologies, the contradiction is displaced. Yonah (1990) has written convincingly that the traditional Sephardic tendency to be hawkish on the territories represents more of an "anti-Arab" position than it does one of ideological commitment to a "greater Israel." Sephardic Jews, he argues, "have always seen their affinity with Arabs and Arab culture as a liability." Thus many have reinterpreted their experience in the Arab lands as one of hostility and poor relations. This "strategy" whether conscious or not is best understood as the struggle by a culturally marginalized group (the Sephardim) to assimilate into mainstream Ashkenazi culture. As proof of the non-ideological position on the territories, Yonah notes that Sephardic Jews make up a disproportionately small part of the West Bank settlers, and are almost totally absent from the most vocal and fervent ideologically-driven groups. Also significant, in the recent election campaign, the groups which competed with Shas for the ethno-religious vote, emphasizing a "greater Israel" message, failed markedly. Given the option of an umbrella identity which is pan-Sephardic (Shas), the territories may, in the end, prove to be an issue which carries less ideological weight in the Sephardic community than had been supposed.

Among those Shas supporters who tend to favor territorial compromise, assimilation strategies are replaced by ones of differentiation. When a haredi Shas supporter was asked "what does it mean to be haredi," he answered "it means that you are willing to give up territories if it will bring peace." The question of the territories was raised by other interviewees in the context of discussions about identity. This can be understood as an attempt by the newly haredi Sephardic Jews to distinguish themselves from their Mafdal past. In arguing that they would be willing to give up territories they are declaring to the world that they are pious men whose primary loyalty is to the study of Torah. They look with disdain on the Mafdal fetishization of the Land of Israel as part and parcel of the misguided religiosity upon which they were raised. It does not mean that they are committed to the necessity of territorial compromise (as the more ideologically committed might argue with a passion). They are open to it as a possibility. This, of course, helps to explain Shas' readiness to join the coalition with either Labor or the Likud. The divisions which run so deep between the larger parties just do not suit the logic of a movement based on ethno-religious unity and directed toward institutionalization of its privileges. Recognition and access to the purse-strings of government has been, and will remain, the driving force behind Shas' coalition politics.

Rabbi Ovadia Yosef with Labor Party Prime Minister, Ehud Barak,

from ha-Rav 'Ovadyah by Ronen Kedem, Yedi'ot Aharonot Books, 2002, page 97.

Building an institutional relationship with the state

Shas has benefited from coalition agreements which have channeled funds to its educational movement, the Wellspring (El Ha'maayan). The Wellspring was established in 1984 soon after Shas' initial entry into Israeli political life. It was modeled on the youth movements of the Mafdal and Labor parties, and legitimized by Shas officials with the argument that the Sephardim had never had a youth movement or educational system tailored specifically to their needs. The Wellspring has grown rapidly in the past eight years and now comprises over 240 branch offices across the country, providing everything from supplemental religious education for youth, bar-mitzvah training, assemblies for women, and lessons with leading rabbis for men. In 1991 Shas' Wellspring organization was recognized as an "official state educational program," earning it legitimacy and funding from the Education ministry. With the creation of a special authority now in that ministry, Shas has brought, for the first time, the haredi educational system under direct state supervision.

The move to bring the haredi educational stream into the realm of state control is indicative of just how much Shas differs from the non-Zionist Agudah party in its attitude toward the institutions of state. For years, Agudah resisted joining government coalitions because of apprehensions about giving legitimacy to the secular state by actively participating in its governance. Taking over the Interior Ministry in 1984, Shas, from the beginning, displayed no such reservations. They have held the Interior Ministry ever since, and have used it as an effective means to channel funds to related religious organizations throughout the country.

In terms of both leadership and the nature of its constituency Shas is also closer in profile to the "Zionist" Mafdal than the "non-Zionist" Agudah. Ovadia Yosef has served for years as an employee of the state under the supervision of Mafdal in the Religion ministry. In his position as Chief Sephardic Rabbi, Yosef was the "official" link between the state and the Sephardic religious community. Though he lost the title by term limitations on the office, Yosef still considers himself the legitimate leader of the Sephardic community in Israel, and wears the decoratively embroidered robe of that office in public appearances.

The vast majority of Shas supporters are products of the Mafdal's state-religious system of education. However, many have rejected the "national-religious" ideology. They have adopted a rigorously ritualized religious lifestyle which is closer in form and appearance to the haredi Agudah. However, unlike followers of Agudah, most Shas supporters have served their full term in the army and still serve in the reserves. More telling, a vast number of Shas voters do not consider themselves haredi, but vote for the party out of a sense of ethnic pride and the promise of cultural renewal. Many might have voted for one of the non-haredi "Zionist" parties like Likud or the Mafdal, as they have in past elections. With these voters, Shas clearly benefited from an increased sense of"Sephardic" identity, set in opposition to both haredi and secular Ashkenazi others. The Likud clearly lost voters to Shas because of perceived discrimination within that party. Months before the elections David Levy, then Foreign Minster, resigned from the Likud amidst accusations that he and his Sephardi contingent had been displaced from leadership positions on the party list. He reconciled himself to the party at the last minute, but the debate had already raged for several weeks. Nasty things were said, enflaming passions on both sides of the ethnic divide. Adding to the election's "ethnic" component, statements by Shach, the Lithuanian haredi leader that "the Sephardim are not fit to run the state" angered the non-haredi Sephardim more than the haredi ones, against whom the attack was lodged. All of these factors added to an increased sense of common "Sephardic" identity right before the elections. A vote for Shas thus carried a protest against both the secular and religious Ashkenazi establishment.

Redefining religious Zionism

Whether Shas can be said to be a participant in a new brand of religious Zionism depends on how you weigh the statements of its leaders and supporters themselves. A haredi follower responded to the question of whether Shas was a "Zionist" party with a qualification: "that depends what you mean by Zionism." He continued,

if you mean the Zionism of Mapai, the Zionism that cut off our payot (earlocks) and forced us to go to secular schools, then "no" we are not Zionists . . . For me if one believes in the Torah of Israel, and the Land of Israel, and the People of Israel, then he is a Zionist. But a real Zionist learns Torah and the mitzvot (commandments). A man who disconnects himself from the Torah is not a Zionist at all. If you ask what I am, or what the haredi community represents, then we are "super-Zionists" . . .

The argument is thus turned on its head. He rejects the secular legitimation of the state, the Zionism which his parents met upon their arrival in Israel. But it is not the notion of a Jewish state that is problematic, it is the particular forms of secularism and cultural domination that are rejected.

Also differentiating Shas from the traditional (Ashkenazi) religious approaches to Zionism, is the tendency to avoid questions over whether the State represents a stage in the messianic process. In interviews, some followers argued that the creation of the state was an important part of the redemptive process; others spoke of the Jewish condition in terms of the metaphor of exile. The redemption/exile dichotomy, a product of ideological debates which have a definitional resonance in the Ashkenazi world, was irrelevant as a common denominator for Shas supporters.

The issue of Zionism struck a bitter cord among many because they felt that it was used against them to deny the legitimacy of their movement. "Everyone says that we are not Zionists, that we do not do the army, that we don't care what happens to the state. But that is not true, many of our supporters do the army, and they are Zionists, and they are right." This statement indicates just how deeply the movement feels that it has been misunderstood. Yet, it also raises another question. While the adults have done their army service, they are bringing up their children to place Torah learning before military service. They distrust the army because they know of the temptations that it may offer to children raised under the careful supervision of the yeshiva environment. So while they do their service, they speak of the hope that their children will be able to defer theirs. From an ideological point of view there seems to be a contradiction. But if one looks from the point of view of a community which feels itself to have been short-changed by the state all these years, support for army deferments can be understood as an attempt to put themselves and the spiritual needs of the Sephardic community before those of the state. It is a rebalancing of sorts.

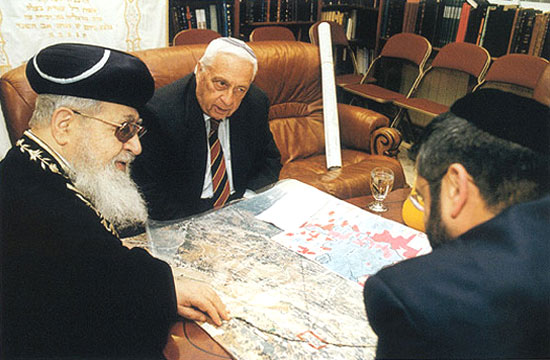

Rabbi Ovadia Yosef with Likud Prime Minister, Ariel Sharon and Shas Interior Minister, Aryeh Deri,

from ha-Rav 'Ovadyah by Ronen Kedem, Yedi'ot Aharonot Books, 2002, page 124.

Conclusion

At a time when the principles of a secular Zionism are subject to readjustment, it seems appropriate to re-evaluate the state of religious Zionism as well. Shas equally rejects the secular socialist principles which many of its constituents confronted upon immigration to the state, as well as the Mafdal version of religious Zionism upon which many were raised. In rejecting both of these ideologies, the movement seems to place itself outside the debate over Zionist principles. But that is only if we accept the Ashkenazi-generated categories and ideological oppositions as constitutive. In this essay, I have shown that both the redemption/exile dichotomy as well as the greater Israel debate have little relevance to a movement based on social and spiritual renewal for the Sephardic community. Contrary to the Ashkenazi political divisions which grew from ideological debates, Shag is a product of identity politics. Its claim as a pan-Sephardic movement is what gives logic and direction to its policies and politics. Shas leaders and supporters alike are involved in an attempt to redefine the terms of the debate and in so doing make their distinctive claims upon the state. Shas is a movement built upon years of frustration and neglect, propelled by a struggle for recognition and legitimacy. To continue to categorize this movement as "non-Zionist" is merely to support the social and political interests that seek to delegitimize Shas and its claim upon the state.

Clearly in terms of its attitude toward the state, Shas has positioned itself somewhere between Agudah and the Mafdal. Perhaps instead of the religious Zionism of the Mafdal, we are now talking about a Religious zionism for Shas. Shas' constituents have difficulty with the language of "Zionism." In many ways it is what they are working against. It didn't "work" for them in the past and now they use it as a reference point from which to assert a vision of renewal. The state as such is not the problem. Even among the more hesitant haredi supporters, there is an important overlapping of their "Torah, Land, and the People of Israel" nationalism with the Zionism of the secular state.

Finally, I would like to underscore the potential effects which the institutionalization of Shas' vision will have for the future of religious Zionism in Israel. Shas has claimed important positions of leadership and responsibility in the state, and stands to benefit from huge cash injections into its Wellspring education system. The special authority in the Education Ministry will assure funding for Shas related schools. With influence in the Ministry of Religion Shas will gain power in local religious councils, provide employment for many of its supporters, and control upcoming appointments for Chief Rabbi. Additionally, Deri's patronage potential in the Interior Ministry will benefit Shas institutions through the allocation of funds to municipalities across the country. In short, Shas is institutionally situated to take advantage of Mafdal's loss, and multiply that into future gains in support and legitimacy for the movement.

Official Shas Party Website

back to top

About the Author

Aaron Willis is a graduate student in Anthropology at Princeton University.

Further Reading on the Shas Party

Shas—The Sephardic Torah Guardians: Religious "Movement" and Political Power by Aaron P. Willis

The Synagogue as Civil Society, or How We Can Understand the Shas Party by Omar Kamil

Rabbi Ovadia Yosef and his "Culture War" in Israel by Omar Kamil

Acknowledgements

This analysis is based on fourteen months of fieldwork in a Sephardic haredi community in Jerusalem. I thank the MacArthur Foundation, the Center of International Studies at Princeton University, and the Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture for their support of this research and its writing. Thanks to Menachem Friedman for his help in the field; to Harvey Goldberg for initially discussing comparisons between Mafdal and Shas; and Mike Aronoff for raising questions about "Zionism." Also, special thanks to Irwin Levin for his review of the international press.

Bibliography

Aran, G. (1986) "From Religious Zionism to Zionist Religion: The Roots of Gush Emunim," in Medding (ed.) Studies in Contemporary Jewry II, Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

Aronoff, M. (1989) Israeli Visions and Divisions: Cultural Change and Political Conflict, Transaction Press, New Brunswick.

Deshen, S. (1970) Immigrant Voters in Israel, Manchester University Press, Manchester .

Diskin, A. (1991) Elections and Voters in Israel, Praeger Publishers, New York.

Friedman, M. (1990) "Jewish Zealots: Conservative versus Innovative,"in Religious Radicalism and Politics in the Middle East, Sivan and Friedman (eds.), State University of New York Press, Albany.

Friedman, M. (1991) The Haredi Society: Sources, Trends, and Processes, The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies, Jerusalem (Hebrew).

Gellner, E. (1969) Saints of the Atlas, Weidenfield and Nicolson, London.

Heilman and Friedman (1991) "Religious Fundamentalism and Religious Jews: The Case of Haredim," in Fundamentalisms Observed, Marty and Appleby (eds.), University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Ravitsky,A (1989) "Exile in the Holy Land: The Dilemma of Haredi Jewry," in Medding (ed.) Israel: State and Society, 1948-1988, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Ravitsky, A (1990) "Religious Radicalism and Political Messianism in Israel," in Religious Radicalism and Politics in the Middle East, Sivan and Friedman (eds.), State University of New York Press, Albany.

Yonah, Y. (1990) "How right-wing are the Sephardim?" in Tikkun, May/June.

Web Editor's Note

This document has been edited slightly to conform to American stylistic, punctuation and hypertext conventions. Other than the inclusion of figures and correction of a few typographical errors, no further changes to the text have been made.

This document is best viewed with 1024x768 pixel screen area.

Reprinted in accordance with U.S. copyright law.

Alabaster's Archive