The Establishment of the Orthodox Rabbinate in Israel

by

Norman L. Zucker

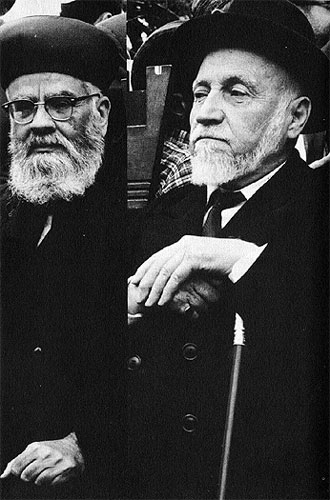

Chief Rabbi Yitzchak Nissim and Rabbi Yaakov Toledano, minister of religious affairs.

from

The Coming Crisis in Israel

Private Faith and Public Policy

1973

Chapter 5

Originally titled "The Establishment of the Orthodox Rabbinate"

pages 76-86

MIT Press

ISBN 0-262-24018-1

Available from Amazon.com

One of the major successes of Israeli theopolitics has been the institutionalization of the Orthodox rabbinate within the state. The Orthodox rabbinate in Israel has been established as a monopoly—neither Reform nor Conservative rabbinic ordinations are recognized—and it is, in part, supported by the state. This monopoly and state support, in conjunction with the coercive tactics of the religious parties in the Knesset, has given the Orthodox rabbinate a good deal of power. It uses this power to further the observance of Orthodox norms, often violating the civil rights of the nonobservant Israeli.

The Orthodox rabbinate has arrived at its present preferred status by stages. The generalized principles that govern the rabbinate and the public order were developed during the Ottoman empire, carried over in their basic patterns by the British mandatory regime, and are now being modifled by Israeli legislation. Under the Turks the millet system recognized special courts for the Jewish and Christian communities. These courts were under the direct control and supervision of the respective religious leaders, who had their powers and jurisdictions clearly delineated in royal charters (firmans) issued by the sultan. The Jewish court was under the Chakham Bashi, the equivalent of a chief rabbi. In theory the Chakham Bashi was the representative of all the Jews of the empire, but in practice the rabbis elected or appointed by the local communities in the cities of Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed, Tiberias, and Jaffa-Tel Aviv were recognized as representatives to the provincial governor. Jewish Community regulations prescribed the electoral composition of its members, and it was an accepted tradition that the Chakham Bashi be a Sephardi.

After the British drove the Turks out of Palestine, the religious courts continued without major change. As the position of Chakham Bashi was vacant, Sir Herbert Samuel, the first high commissioner, appointed a commission to make proposals for establishing a supreme religious authority. The committee recognized the influx of Ashkenazic Jews, who by now outnumbered the Sephardim, and proposed a joint Chief Rabbinate and Chief Rabbinical Council to be selected by a special assembly. In February 1921 the assembly elected Rabbi Avraham Y. Kook as Ashkenazic chief rabbi and Rabbi Yaakov Meir as Sephardic chief rabbi. A hierarchical court structure—local rabbinical tribunals, an appellate court, and the Joint Supreme Court in Jerusalem—was established. These rabbinical courts were given exclusive jurisdiction in matters of marriage, divorce, alimony, confirmation of wills, and jurisdiction in any other matter of personal status (for example, maintenance, guardianship, legitimation, adoption of minors, and so on) where the parties to the action gave their consent. The Natore Karta and the Agudat Israel objected to this arrangement and vehemently insisted on their own separate rabbinical authorities. These objections were ultimately recognized by the Religious Communities Organization Ordinance, which provided for the overall secular and religious framework of the Jewish Community in Palestine while permitting any Jew to opt out of the Community.1

With the termination of the Mandate the secular institutions of the Jewish Community were replaced by new governmental machinery appropriate to a sovereign state. The religious institutions continued to exist and were, with some modifications through a variety of Knesset acts, over a period of time incorporated into the body politic. In addition, a Ministry of Religious Affairs was created to deal with both the Jewish and non-Jewish communities, although in actual practice the Ministry's major work is primarily with Orthodox Jewish concerns.

All the state's religious institutions are interrelated, although there is a functional administrative separation. The Chief Rabbinate and the Chief Rabbinical Council (a group of senior rabbis) control Jewish religious authority and decide on the interpretation of Jewish law (halakhah), and in the process are vested with legal and administrative state powers. It is the Chief Rabbinate through its secretariat which supervises and certifies rabbinical ordination, certifies rabbis to teach in religious state schools, controls the training of religious judges, the licensing and performance of religious scribes and circumcisers, and enforces some of the dietary regulations; for example, the rabbinate certifies that imported meat and locally produced foodstuffs are kosher.

The Ministry of Religious Affairs, as a natural result of theopolitics, has become the fief of the religious parties (primarily the NRP). It works closely with the established rabbinate and actively promotes Orthodox Judaism. The Ministry is responsible to the Knesset for the general administration of the rabbinical courts and holy places and for the supervision of dietary regulations in government institutions and public places. It also supervises the production and export of ritual articles. Working with the rabbinate and the local religious councils, the Ministry helps finance talmudic academies (yeshivot) with general funding and capitation grants to needy students and contributes money toward the building and maintaining of synagogues. Furthermore, as a recent Government Yearbook notes, "Any local applicant, individual or institutional, gets religious books and ritual appurtenances gratis or at token cost from the Ministry, and publication of religious writings is subsidized." The Ministry supports a public council that, by information and propaganda, seeks to combat desecration of the Sabbath. There are also a committee to develop the sanctity of Mount Zion and a fund to counter conversionist activity among impoverished Jews. The Ministry through its Divisions maintains contact with the Diaspora, disseminates religious information, carries out research, and acts as a coordinator of religious events and ceremonies.2

The local religious councils and the religious committees in the smaller localities, as their names imply, deal on the local level with a variety of public services of a religious nature. They maintain ritual baths, supervise ritual slaughter, issue certificates of kashrut (dietary fitness), and register marriages and divorces, all of these being functions for which they receive fees. Fees alone, however, cannot support the councils' functions, and financing is provided by the state, which contributes one-third, and the local authorities, which contribute two-thirds, to the basic budgets.3

The minister of religious affairs, a secular political official, also plays an important role, which may have far-reaching political and theological overtones, in the ordinary administration of his office and in the elective process by which the two chief rabbis and the Chief Rabbinical Council are constituted. A neutral or hostile minister, technically a possibility if a strong secularist antireligious government ever achieves a solid power base, could attempt either to neutralize or to hamper state support to the rabbinate. To date, however, the Ministry has acted to enhance the power of the Orthodox, particularly since 1961, when Dr. Zerah Warhaftig of the National Religious Party, an able exponent of his party's principles and objectives, became minister of religious affairs. As to the minister's role in guiding the theological direction of the organized state rabbinate, a cursory history of the Chief Rabbinate-Chief Rabbinical Council elections is illustrative.

As noted previously, in 1921 a special assembly elected the Ashkenazic and Sephardic chief rabbis. When Avraham Kook, the Ashkenazic chief rabbi, died in 1935, an electoral assembly chose Dr. Yitzchak Ha-Levy Herzog to succeed him and reelected the incumbent Sephardic Chief Rabbi Meir. The electoral assembly convened again, four years later, after the death of Rabbi Meir and elected Rabbi Ben-Zion Ouziel Sephardic chief rabbi. The death of Rabbi Ouziel in 1953 created the first vacancy for the office of a chief rabbi since the establishment of the state.4

The tradition of reelecting the incumbent chief rabbi—in this instance, Ashkenazic Rabbi Herzog—was upheld, and his office was filled without a contest. But at the same time a bitter contest over the vacant Sephardic chief rabbi's seat developed between Rabbi Yitzchak Nissim, who was identified with the National Religious Party, and Rabbi Yaakov Toledano, who was a nonparty man. Rabbi Nissim won the election. Rabbi Toledano retired to his private pursuits but returned to the public scene in 1958 when Prime Minister Ben-Gurion, in an attempt to break the growing power of the politicized Orthodox, appointed him minister of religious affairs. The basis for future party and personal clashes had now been laid. Under the election regulations of the rabbinate, new elections had to be held in 1960, but the orderly application of the regulations was disturbed by events. Before the 1960 elections were held, Ashkenazic Chief Rabbi Herzog died, thereby giving Minister Toledano an opportunity to change the rules without violating the tradition of reelecting an incumbent. In drawing up the 1960 election rules, Rabbi Toledano stipulated that a candidate for the office of chief rabbi must be an Israeli citizen and under seventy years of age. (Rabbi Nissim, the incumbent Sephardic chief rabbi, was not affected by the new rules, but these restrictions appeared to be an attempt to rig the elections against the two major Ashkenazic candidates affiliated with the NRP, Rabbi Joseph Soloveichik of the United States, and Rabbi Issar Y. Unterman, who exceeded the age limitation, in favor of Rabbi Shlomo Goren, a nonparty man.) After considerable discussion, Minister Toledano withdrew his objection to non-Israeli candidates but stood firm on the age limitation. Toledano argued, with some merit, that since a chief rabbi is head of the religious courts, and the law requires a religious judge (dayyan) to retire at seventy-five, a man in his seventies could not complete his five-year tenure without violating the law.5 The Chief Rabbinical Council refused to accept this argument and declined to appoint anyone to the election committee. This refusal to appoint their share of the electoral committee was followed by an even more adroit political move. The Chief Rabbinical Council proclaimed a boycott of the rabbinical elections and called upon the observant to decline to be nominated to the electoral college that was to choose the two chief rabbis and the six other rabbis who would comprise the new Chief Rabbinical Council. With the issue deadlocked, rabbinate elections were not held as scheduled.

The Chief Rabbinate, that is, Rabbi Nissim and the Council, were operating in contravention of their tenure limitation. The rationale for the continued operation of the Chief Rabbinate under questionable legal standing, it was reported, was to make the Mapai-led government bear the responsibility for whatever inconvenience the public might experience because of the government's refusal to extend the sitting rabbinate's tenure. The tactic of continued operation forced the government to correct the anomalous situation by special Knesset legislation that legalized the rump Chief Rabbinate. Prolonged attempts to break the impasse between Rabbi Toledano, who was supported by Ben-Gurion, and the Chief Rabbinical Council, which was headed by Rabbi Nissim and supported by the NRP, came to naught. In 1961 Rabbi Toledano died, and after the elections of that year Mapai, as a necessity of coalition bargaining, conceded the post of minister of religious affairs to the National Religious Party. Nonetheless, it was not until 1964 that elections for the Chief Rabbinate were held.6

The rabbinical elections of that year were widely considered to be a contest between the Orthodox traditionalists supported, in the main, by the National Religious Party, and the more liberal or flexible Orthodox elements that had the encouragement of Mapai. Rabbi Goren, then forty-seven, a widely respected scholar and colorful senior chaplain of the Israeli defense forces, ran for the office of Ashkenazic chief rabbi against Issar Y. Unterman, then approaching seventy-eight. Expressing the views of the "modernists" Rabbi Goren stated: "The Rabbinate so far has not awakened to the fact that there is a Jewish State, and that halakhah must be brought up to date to make the State viable." 7 Rabbi Goren long before the election had urged the reestablishment of a Sanhedrin (grand religious council) to interpret and resolve issues of Jewish life in view of scientific and technological change and the establishment of a Jewish state.8 The "flexible" Orthodox oppose, along with the traditional Orthodox, deviations from biblical and talmudic law, but they emphasize the need for flexibility. The "modernists" made a good showing, but the strict traditionalists retained control. Unterman defeated Goren by three votes for the position of Ashkenazic chief rabbi. The incumbent Sephardic chief rabbi, Nissim, was returned to office by a substantial margin, but, significantly, the candidacy of an incumbent had been challenged. With the Ashkenazic post now occupied for the first time in six years, a plenary Chief Rabbinate was now in office.9

Unterman was installed as chief rabbi in a colorful ceremony that underscored the official ties between the Orthodox rabbinate and the state. The president, prime minister, president of the Supreme Court, cabinet ministers, Knesset members, and a host of other dignitaries viewed the proceedings. The new chief rabbi indicated in his inaugural address his intention of taking a strong stand against missionary activity and expressed the hope that he and the Sephardic chief rabbi would succeed in uniting Jewry.10 This expression of unity, however, was but a pious hope. The fanfare and speeches could not conceal the substantive issues arising out of the unsettled authority of the Chief Rabbinate. It could not be forgotten that the Chief Rabbinate and the Chief Rabbinical Council, although religious institutions, were considered public bodies because secular law regulated the way they were financed and constituted and were, as such, subject to judicial control of the secular High Court of justice, even in some matters of religious rulings.

Pointedly absent from the inauguration ceremonies were those among the devout who did not recognize the authority of the Chief Rabbinate: the adherents of Agudat Israel who have their own final authority, a council of Torah sages, the Natore Kartaites, and others who follow their own leaders. Among the Orthodox who accept the authority of the established rabbinate, there were many who were disenchanted by the delays and distressed by the acrimony and politicking that accompanied the establishment of the election machinery. They wondered if the political interplay between secular Mapai and the religious parties in the coalition was in the best interests of the rabbinate. There was present, they reasoned, the deplorable possibility that the rabbinate could become subject to official pressure and influence. They feared for the independence and prestige of the rabbinate. Others among the Orthodox pointed out that religious leaders should establish their authority by virtue of their own personal qualities and the general consent of the faithful, without any need for formal electoral procedure based on secular legislation. Every ordained rabbi is equal in spiritual authority to all other rabbis. Rabbinical luminaries had, in the past, established their reputations and enjoyed the widespread respect and honor of their followers without such procedures. Piety, scholarship, justice, kindness, and wisdom could not be guaranteed or ensured by an election. And finally, there were those who questioned the advisability of or need for a dual Chief Rabbinate. They argued that the differences between the Ashkenazim and the Sephardim, although sociological—and at that the "Sephardic" classification was imprecise!—were not theological. For a lengthy period prior to the elections the Rabbinate had functioned with only one Chief Rabbi. There was but one Torah and one halakhah.

Under Unterman and Nissim the Chief Rabbinate declined in prestige. The Askenazic Chief Rabbi frequently was at odds with the Sephardic Chief Rabbi. It appeared that both rabbis were devoting more energy to preserving prerogative and form than to adjusting halakhah to the realities of a Jewish state. Little spirituality emanated from the Chief Rabbinate. As their term drew to a close in 1969, all the previous issues that roiled the rabbinate were resurrected. The advanced age of the incumbents—Rabbi Unterman was in his eighties and Rabbi Nissim in his seventies—again suggested that an upper age limit be set. Also, the philosophical and personality clashes between the two men only reinforced those critics who argued against a dual Chief Rabbinate. The cabinet, in fact, at one point discussed and dismissed the possibility of writing into the rabbinical elections law a ten-year limit to the dual Chief Rabbinate. However, after much bickering between the Alignment and the National Religious Party over the composition of the electoral college, and after several extensions of the Chief Rabbinate's allotted term, elections for the office of Ashkenazic and Sephardic Chief Rabbis and the Chief Rabbinical Council were held in October 1972. As in the previous election, Rabbi Goren, who had retired from the military chaplaincy to become Tel Aviv's Ashkenazic Chief Rabbi, challenged Rabbi Unterman. Rabbi Nissim was challenged by the highly regarded Sephardic Chief Rabbi of Tel Aviv, Ovadia Yosef. In a precedent-breaking election the elderly incumbents were defeated by Goren and Yosef, both in their fifties. Moreover, some of the more conservative members of the outgoing Chief Rabbinical Council were defeated for reelection.

Rabbis Goren and Yosef probably will direct some of their efforts to the adaptation of halakhah to the needs of Israeli society. But it remains to be seen if respect and regard can be restored for the institution of the Chief Rabbinate. The Chief Rabbinate is now solidly built into the Israeli political system. It enjoys institutional preferment and state support. Its very presence in the Holy Land automatically cloaks it with tremendous potential for prestige and spiritual leadership. To date, however, its potential for spiritual leadership remains unfulfilled. The Orthodox Rabbinate, by concentrating on consolidating its position, has diminished its spiritual standing and has caused rifts with the Reform and Conservative branches of Judaism.

back to top

Notes

1. Norman Bentwich, "Chief Rabbis—and An Office that Dates from Ottoman Times," Jerusalem Post Weekly, Overseas Edition, March 13, 1964, p. 7; Amnon Rubinstein, "Law and Religion in Israel," Israel Law Review, Vol. 2, No.3 (July 1967), 384-388.

2. Reuven Alcalay, ed., Israel Government Yearbook 5728 (1967/68) (Central Office of Information, Prime Minister's Office, Israel: The Government Printing Press, 1968), pp. 271-273. The quote is on page 272.

3. The councils and committees are under the general supervision of the Ministry of Religious Affairs and their staffs come under the civil service regulations. The number of council members is determined by the minister of religious affairs, but in no case may this number exceed the number of members of the local authority. Appointments to the religious councils are renewed quadrennially on a shared basis. The minister of religious affairs and the local authorities each appoint 45 percent of the total of the council membership, leaving the selection of the remaining members to the local rabbinate, and the appointments must be approved by all parties. If the minister of religious affairs, the local authority, and the local rabbinate cannot reach an agreement, the question is referred to a committee composed of the ministers of religious affairs, justice, and the interior, or their representatives. Should the committee be unable to reach agreement, the matter is brought before the government for a final decision. This peculiar arrangement for the division of religious council seats is a result of an agreement between Mapai and the NRP. An attempt to challenge in the courts this formula for the allocation of council seats was unsuccessful. Where a local authority has no religious council, such as in a new development town, the minister for religious affairs is empowered to establish one.

In 1964 the Jerusalem Religious Council, one of the more important councils, for the first time had its activities scrutinized by the state controller. In his report the controller took note of, among other things, the sloppy accounting procedures used, a quarrel between the council members belonging to the dominant National Religious Party and the council members of Agudat Israel (who do not recognize the Chief Rabbinate and only recently had begun to participate in the council), the inactivity of the council's committees, failure to maintain complete records of kashrut inspections, and failure to give written explanations of refusals to renew kashrut certificates. The present system of religious councils was last extended in 1967. At that time during the Knesset debate, it was generally conceded that the religious council system had numerous defects, but, in the absence of working out a more satisfactory system, the councils were to be extended. As of 1969 there were 179 religious councils and 320 religious committees. For further details concerning religious councils, see Yehoshua Freudenheim, Government in Israel (Dobbs Ferry, New York: Oceana Publications, Inc., 1967), pp. 95-96; Rubenstein, "Law and Religion in Israel," 398-399; Alcalay, Israel Government Yearbook 5728, p. 37; Misha Louvish, ed. Facts About Israel: 1969 (Jerusalem: Information Division, Ministry for Foreign Affairs, Keter Books, 1969), p. 66.

4. In 1935 the Electoral Assembly was composed of 42 rabbis recognized by the Jewish Community rules and 28 laymen nominated by the General Council (Vaad Leumi). Under the 1954 election rules, the outgoing Chief Rabbinical Council and the minister of religious affairs each appoint 4 members to a committee that selects 42 rabbis for the electoral college. These rabbis, together with 28 laymen chosen by the local religious councils comprise a 70-man electoral college. Joseph Badi, Religion in Israel Today: The Relationship Between State and Religion (New York: Bookman Associates, 1959), pp. 32-35; Freudenheim, Government in Israel pp. 92-95.

5. In order to resolve the anomaly of having a chief rabbi who would violate the Dayyanim Law if he served as president of the Grand Rabbinical Court when over seventy-five, the law was amended in 1966. Under the new rules the principle of a chief rabbi not serving as a dayyan when over seventy-five was retained, but a superannuated chief rabbi was permitted to exercise certain powers and duties he would have exercised in his capacity as a dayyan. See Henry E. Baker, "Legal System," in The Israel Yearbook: 1967, ed. L. Berger (Israel: Israel Yearbook Publications Ltd., 1967), pp. 85-86.

6. The 1964 rabbinical elections were held under regulations that specifically provided that they were to be in force for that election only. The Mandatory Regulations served as a model, as in the previous rabbinate election, but further changes were also introduced. The electoral committee consisted of nine members (previously eight) of which four were appointed by the government on the recommendation of the minister of religious affairs, and four were elected by the Chief Rabbinical Council. The chairman, the ninth member, was elected by the eight members of the committee. The membership of the Electoral Assembly was broadened to 125, the principles of parity between Ashkenazic and non-Ashkenazic communities retained, along with the division of the Electoral Assembly members into two groups: 75 rabbis and 50 representatives of the religious councils. The latter group had to affirm by written statement that their attitude toward Jewish tradition was "positive." Freudenheim, Government in Israel, pp. 92-95, gives the details and nuances of the election mechanism.

7. Jerusalem Post Weekly, Overseas Edition, March 20, 1964, p. 2.

8. The reestablishment of a Sanhedrin, Rabbi Goren urged in a visit to the United States, could "fill the vacuum in world Jewish life because of the present lack of an effective rabbinic authority which could issue binding orders and rulings on difficult religious matters." A Sanhedrin would, Goren stated, "raise immeasurably the prestige, stature, and dignity of Orthodox Jewry" and would make "Talmudic and Biblical codes an accepted part of the behavioral patterns of Jews in their multifarious activities." The idea of a Sanhedrin to modernize archaic religious regulations was not new. Chief Rabbi Ouziel previously had called for the setting up of a Sanhedrin. And Rabbi Yehudah L. Maimon, the Mizrachi leader who was Israel's first minister of religious affairs, during his tenure of office, strongly supported the idea of convening a Sanhedrin. Maimon's call for a Sanhedrin was vigorously opposed by the ultra-Orthodox who disputed his belief that the establishment of a Jewish state marked the beginning of Messianic redemption. New York Times, December 2, 1962, 149: 3 for Goren quote; ibid., February 4, 1950, 4: 6 for Rabbi Maimon's views on the desirability of calling a Sanhedrin.

9. English language coverage of the rabbinate elections, background and results, appeared in both the New York Times and the Jerusalem Post. Specifically, see the New York Times, March 15, 1964, 46: 6; ibid., March 18, 1964, 8: 3; the Jerusalem Post Weekly, Overseas Edition, January 17, 1964, p. 2; ibid., January 24, 1964, p. 1; ibid., March 10, 1964, pp. 1 and 2.

10. Jerusalem Post Weekly, Overseas Edition, April 17, 1964, p. 2.

Web Editor's Note

This document has been edited slightly to conform to American stylistic, punctuation and hypertext conventions. Other than a few clarifying additions to make it easier to read as a standalone piece, no further changes to the text have been made.

This document is best viewed with 1024x768 pixel screen area.

Reprinted in accordance with U.S. copyright law.

Alabaster's Archive